Protein Intake and Weight Loss Tendency: The Genetics

Table of Contents

Understanding Protein Intake and Weight Loss

Proteins are complex molecules that play many critical roles in the body. They are required for the structure, function, and regulation of the body’s tissues and organs.

Proteins are one of the three types of nutrients that provide energy to the body, along with carbohydrates and fats.

Amino Acids and Protein Structure

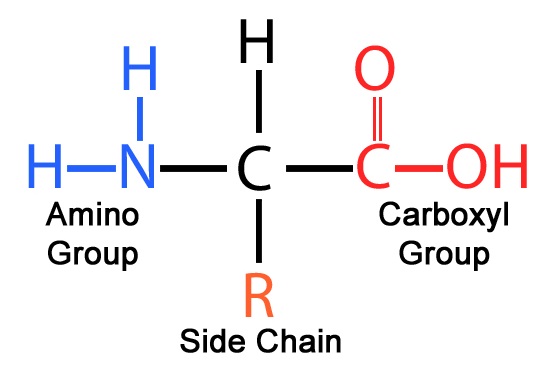

Proteins are made up of smaller units called amino acids, which link together in long chains. There are twenty different types of amino acids that can be combined to form a protein. The sequence of amino acids determines each protein’s unique 3-dimensional structure and specific function.

Each amino acid contains an amino group (NH2), a carboxyl group (COOH), and a side chain that is specific to each amino acid. The side chain can make an amino acid behave like an acid or a base, be hydrophilic (water-loving) or hydrophobic (water-fearing), or even change the shape of the protein when incorporated into the chain.

Fun Fact: Proteins fold into complex shapes due to the chemical properties of their amino acids. The three-dimensional structure of a protein is crucial for its function. If a protein loses its shape, in a process called denaturation, it often becomes nonfunctional.

Functions of Proteins

Proteins have numerous roles in the body. Here are some key ones:

- Enzymes: Many proteins act as enzymes, molecules that speed up chemical reactions in the body. For instance, digestive enzymes help break down food into smaller molecules that your body can absorb.

- Structural proteins: These provide structure and support for cells. On a larger scale, they also allow the body to move. Examples include collagen, elastin, and keratin, which make up much of the skin, hair, and nails.

- Transport proteins: These proteins move molecules around the body. Hemoglobin, for example, transports oxygen through the blood.

- Antibodies: These proteins bind to specific foreign particles, such as viruses and bacteria, to help protect the body.

- Hormones: Some proteins function as hormones, which are chemical messengers that help coordinate the body’s actions. Insulin, for example, helps regulate glucose levels in the blood.

- Receptors: Proteins on the surface of cells act as receptors, receiving signals from the environment and communicating them to the inside of the cell.

Proteins and Diet

In our diet, we need to consume proteins or their building blocks, amino acids.

The human body can create some of these amino acids, but nine of them, known as essential amino acids, must be obtained from food.

Dietary protein is found in foods like meat, fish, eggs, dairy products, legumes, and nuts.

After we consume these foods, our bodies break down the proteins into amino acids, then reassemble those into new proteins that help do everything from building tissues to boosting our immune system to helping our brain function properly.

Section Summary

Understanding the role and function of proteins is fundamental to understanding life itself, given their essential roles in virtually all biological processes.

Exploring the Diverse Sources of Proteins

Proteins can be found in both animal and plant-based sources. Animal-based sources include meat, fish, dairy, and eggs.

Plant-based sources encompass legumes, nuts, seeds, and certain grains like quinoa and buckwheat.

The Molecular Dynamics of Proteins: A Closer Look

At a molecular level, proteins are made up of long chains of amino acids, which are linked together by peptide bonds.

The sequence of amino acids and the shape of the protein determine its function in the body.

Critical Roles Proteins Play in Our Bodies

Proteins are a fundamental component of all cells in the body and play crucial roles in numerous biological functions. They are often referred to as the building blocks of life. Here are some of the critical roles that proteins play in our bodies:

- Cell Growth and Repair: Proteins are essential for the growth and repair of cells in the body, including muscle cells, skin cells, and hair cells. They’re the primary component of muscles and are required for muscle building and repair.

- Enzyme Production: Many proteins function as enzymes, which facilitate chemical reactions in the body. They play a critical role in metabolic processes, including digestion and energy production.

- Hormone Production: Some proteins function as hormones, which are chemical messengers that transmit signals throughout the body. Examples include insulin, which regulates blood sugar levels, and growth hormone, which influences cell growth and repair.

- Immune Function: Proteins form the building blocks for many components of the immune system, including antibodies and immune system cells. Antibodies are proteins that neutralize pathogens such as bacteria and viruses, while other proteins help to regulate immune responses.

- Transport and Storage: Some proteins carry and store important molecules. For example, hemoglobin is a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body.

- Structural Support: Some proteins provide structure and support for cells. For example, collagen is a protein that provides structure and elasticity to the skin, tendons, ligaments, and bones.

- Nutrient Regulation: Proteins are involved in nutrient regulation in the body. For example, they help regulate the balance of fluids in your body, and they’re involved in the transport of nutrients and other substances in your blood.

Section Summary

Proteins play an essential role in nearly every biological process, and it is crucial to maintain adequate protein levels to support these functions.

Interesting Facts about Proteins

- Most Abundant Substance in the Body After Water: Proteins make up approximately 20% of the human body’s mass, following water. They’re present in every cell and tissue, serving as crucial building blocks.

- Existence of Essential and Nonessential Amino Acids: Proteins are made up of smaller units known as amino acids. While our bodies can produce some amino acids (nonessential), others (essential) must be obtained from the diet.

- More Than Just Meat: While meat is a well-known source of protein, proteins are also plentiful in plant foods. Foods such as lentils, chickpeas, quinoa, and nuts are rich in proteins.

- Shapeshifters of the Cellular World: Proteins can change their shape, a property called conformational flexibility. This allows them to perform different functions, like acting as enzymes, transporting molecules, or sending signals.

- Proteins Can Misfold: Occasionally, proteins misfold into incorrect shapes, leading to diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Certain environmental and genetic factors can increase the risk of protein misfolding.

Tracing the Historical Footprints of Proteins

The understanding of proteins has come a long way since the early 19th century when Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius first coined the term “protein” derived from the Greek word “proteios”, meaning “primary” or “in the lead”.

Recommended Daily Allowance for Proteins

The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein is 46 grams per day for women and 56 grams per day for men, though this can vary based on factors such as age, activity level, and overall health.

The Interplay Between Genetics, Protein Consumption, and Weight Loss

The interplay between genetics and protein consumption, particularly in the context of weight loss and body composition, is a topic of ongoing research in the field of nutrigenomics.

Nutrigenomics is the study of the effects of food and food constituents on gene expression.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that individual genetic variation can influence how our bodies process and use dietary protein.

There are several genetic variants, also known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), that have been found to affect protein metabolism and thus may influence body weight and composition.

For instance, the FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated) gene is known to be a significant genetic factor in obesity.

Some studies have shown that individuals with certain variants of this gene may have a better weight loss response to high-protein diets.

For a more in-depth analysis of the FTO gene in different aspects of nutrition, you read all our articles on nutrigenomics.

Similarly, variations in genes like LEPR, GCKR, LIPC, PPARγ, MTNR1B, and TFAP2B can also influence how the body metabolizes and responds to dietary protein.

Some of these variants can affect satiety responses, protein and fat metabolism, insulin response, and even where the body tends to store fat.

1. LEPR (Leptin Receptor Gene):

The leptin receptor gene (LEPR) codes for a protein that is fundamental in the body’s regulation of energy intake and expenditure, including appetite and hunger, metabolism, and behavior.

Variations in the LEPR gene may influence satiety response to dietary protein.

This means that individuals with certain variants might feel more satisfied after consuming protein-rich meals, which could impact their overall caloric intake and potentially contribute to weight management.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the LEPR gene variants

2. GCKR (Glucokinase Regulatory Protein Gene):

The GCKR gene plays a role in glucose metabolism by regulating glucokinase, an enzyme that enables the breakdown of glucose in the body.

Variants of the GCKR gene have been associated with alterations in how the body processes both carbohydrates and proteins.

The specific effect on protein metabolism is still under study, but it is hypothesized that this could affect how effectively the body uses dietary protein and thus influence body weight and composition.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the GCKR gene variants

3. LIPC (Hepatic Lipase Gene):

The LIPC gene produces an enzyme called hepatic lipase, which plays a significant role in the metabolism of lipoproteins (complexes of fat and protein that transport fats through the bloodstream).

Variants in LIPC might affect fat and protein metabolism, influencing how the body responds to different diets and potentially playing a role in body weight and composition.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the LIPC gene variants

4. PPARγ (Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Gene):

PPARγ is a key regulator of adipocyte differentiation and plays a significant role in fat storage.

Certain genetic variants have been linked to increased fat storage, affecting body composition.

Variations in this gene may interact with dietary protein, affecting how the body processes and stores dietary fats and proteins.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the PPARγ gene variants

5. MTNR1B (Melatonin Receptor 1B Gene):

The MTNR1B gene is involved in insulin secretion and has been linked with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

The interaction between variations in this gene and dietary protein is not entirely understood, but it could influence how the body metabolizes and uses different nutrients, including proteins.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the MTNR1B gene variants

6. TFAP2B (Transcription Factor AP-2 Beta Gene):

The TFAP2B gene has been linked to a higher BMI and obesity risk.

Certain variations in this gene might impact how the body metabolizes dietary protein and other macronutrients.

This could potentially influence body weight and composition, although more research is needed to fully understand these interactions.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the TFAP2B gene variants

It’s important to note that the relationships between these specific genetic variants and protein intake are complex and influenced by a multitude of factors, including other genetic and environmental variables.

Therefore, while these gene variants provide some insights, they don’t tell the whole story.

Understanding the interplay of genetics, diet, and other factors can help in developing personalized dietary plans for optimal health and weight management.

Therefore, understanding an individual’s genetic makeup may help to inform dietary recommendations, including protein intake, for weight loss or weight management.

For example, a person with certain genetic variants may benefit more from a high-protein diet, while another person with a different genetic makeup may need a different balance of macronutrients for optimal weight management.

However, it’s essential to keep in mind that genetics is only one part of the story.

Non-genetic factors, such as overall diet quality, physical activity levels, sleep, and other lifestyle factors, also significantly impact weight loss and weight management.

Section Summary

The interplay between genetics and protein consumption provides a fascinating glimpse into the complexities of weight management and personalized nutrition, with many opportunities for further research.

The Impact of Non-Genetic Elements on Saturated Fats and Weight Increase

Non-genetic factors, such as diet, lifestyle, and environmental factors, also significantly impact weight gain related to saturated fats. Overconsumption of foods high in saturated fats can contribute to weight gain and other health issues.

Effects of Excessive Protein Intake on Weight Loss

While a high-protein diet can aid in weight loss, overconsumption may lead to digestive issues, kidney damage, and nutrient deficiencies.

Balancing protein intake with other nutrients is essential for healthy weight loss.

The Health Implications of Protein Deficiency

Protein is a critical macronutrient that plays a role in virtually every process in the body, from building and repairing tissues to producing enzymes, hormones, and antibodies.

Inadequate protein intake can lead to a number of health problems. Here are some of the key implications of protein deficiency:

- Muscle Wasting and Weakness: Proteins are the building blocks of muscles. Insufficient protein can lead to muscle wasting, leading to weakness and reduced strength. This condition, called sarcopenia, is more common in older adults but can occur at any age in response to protein deficiency.

- Poor Recovery from Injuries: Protein plays a key role in wound healing. A deficiency can delay the healing process, prolonging recovery from injuries, surgeries, or wounds.

- Reduced Immune Function: Proteins form the building blocks for many components of the immune system, including antibodies and immune system cells. A deficiency can result in a weakened immune system, leading to a higher susceptibility to infections.

- Growth and Development Issues in Children: Protein is crucial for growth and development during childhood and adolescence. Inadequate intake can lead to growth failure, delayed developmental milestones, and reduced cognitive function in children.

- Skin, Hair, and Nail Problems: These tissues are primarily made up of protein, specifically keratin. Protein deficiency can lead to thinning hair, brittle nails, and skin problems like rashes or flaky skin.

- Edema: This condition, characterized by swelling in the hands, feet, and legs, is a common symptom of severe protein deficiency. It’s due to an imbalance in the proteins that keep fluid in the bloodstream.

- Anemia: Since protein is required for the production of hemoglobin – the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body – a deficiency can lead to anemia, causing symptoms like fatigue and weakness.

It’s important to note that severe protein deficiency is relatively rare in developed countries, where most people consume adequate amounts of protein.

However, certain populations may be at a higher risk, including those with certain health conditions, older adults, and individuals following restrictive diets.

Optimal Protein Intake for Weight Loss

Balancing protein intake in your diet is critical for effective weight loss.

Here are some guidelines to follow for appropriate protein consumption:

- Understand Your Protein Needs: Protein needs vary depending on your age, sex, physical activity level, and overall health status. The Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) for protein is 46 grams per day for women and 56 grams per day for men, but this can increase with increased physical activity or in certain health conditions.

- Choose High-Quality Protein Sources: Prioritize lean protein sources like chicken, turkey, fish, and low-fat dairy over processed meats, which can be high in saturated fat and sodium. Plant-based proteins, such as legumes, nuts, seeds, and whole grains, are also excellent choices.

- Combine Protein with Fiber-Rich Foods: Pairing protein with fiber-rich foods can help you feel fuller for longer. This combination can aid in weight loss by reducing overall calorie intake.

- Spread Protein Intake Throughout the Day: Rather than consuming a large amount of protein in one meal, aim to distribute your protein intake evenly throughout the day. This can help optimize muscle protein synthesis and keep you feeling satiated.

- Monitor Your Overall Caloric Intake: While protein can aid in weight loss, it’s still crucial to maintain a balanced diet and monitor overall calorie consumption. Remember, weight loss requires a caloric deficit.

- Adjust Protein Intake If Necessary: For individuals engaged in intense physical training or specific diet plans, higher protein intake might be beneficial. However, always consult with a healthcare provider or dietitian to assess your needs before making significant dietary changes.

Remember, while protein is important, a healthy diet should be balanced, containing adequate amounts of carbohydrates and fats as well.

In Conclusion: The Impact of Proteins on Weight Management

Proteins play a vital role in weight management.

By understanding the sources, functions, and recommended intakes, we can make informed dietary choices for better health and effective weight management.

Citations and Additional Readings

- Proteins: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (2023). Medlineplus.gov. Retrieved from: [https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article]

- Zhang X, Qi Q, Zhang C, Smith SR, Hu FB, Sacks FM, Bray GA, Qi L. FTO genotype and 2-year change in body composition and fat distribution in response to weight-loss diets: the POUNDS LOST Trial. Diabetes. 2012 Nov;61(11):3005-11.

- Wang T, Huang T, Heianza Y, Sun D, Zheng Y, Ma W, Jensen MK, Kang JH, Wiggs JL, Pasquale LR, Rimm EB, Manson JE, Hu FB, Willett WC, Qi L. Genetically determined physical activity and its association with circulating proteins. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021 Apr;45(4):796-806.

- Haupt A, Thamer C, Staiger H, et al. Variation in the FTO gene influences food intake but not energy expenditure. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009;117(4):194-197.

- Institute of Medicine (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrates, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. The National Academies Press.

- Paddon-Jones D, Westman E, Mattes RD, Wolfe RR, Astrup A, Westerterp-Plantenga M. (2008). Protein, weight management, and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 87(5):1558S-1561S.

- Leidy HJ, Clifton PM, Astrup A, Wycherley TP, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Woods SC, Mattes RD. (2015). The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 101(6):1320S-1329S.

- Phillips SM, Chevalier S, Leidy HJ. (2016). Protein “requirements” beyond the RDA: implications for optimizing health. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 41(5):565-572.

- Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Gatto GJ. (2002). Biochemistry. 5th edition. New York: W H Freeman.

- Nelson DL, Cox MM. (2008). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. 5th edition. New York: W H Freeman.

- Gropper SS, Smith JL, Groff JL. (2008). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism. 5th edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Written By

Share this article