Emotional Eating: Bridging the Gap Between Genetics and Behavior

Table of Contents

The Science Behind Emotional Eating?

The science behind emotional eating is a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and environmental factors.

From a neurobiological perspective, it involves various brain regions and neurotransmitter systems, while the genetic aspect hints at our inherited predispositions. A

t the same time, psychological and environmental influences shape these innate tendencies into behavior.

The Neurobiology of Emotional Eating

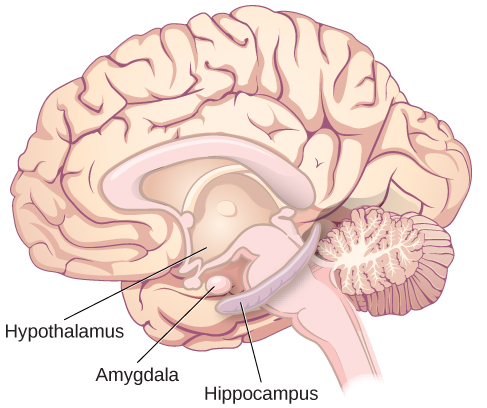

Emotional eating primarily involves the brain’s reward system, a network of structures responsible for pleasure and satisfaction.

Two key components of this system are the hypothalamus, which regulates hunger and satiety, and the amygdala, which processes emotions.

When you experience negative emotions, the amygdala activates and can override the hypothalamus’s signals, leading you to eat even when you’re not physically hungry.

Several neurotransmitters regulate these processes, including dopamine and serotonin. Dopamine is often called the “feel-good” neurotransmitter because it’s associated with feelings of pleasure and reward.

When you eat palatable foods (particularly high-sugar and high-fat foods), your brain releases dopamine, creating a sensation of pleasure.

However, repeated overeating can lead to reduced dopamine receptor density, meaning that over time, you need to eat more to feel the same level of satisfaction, which can trigger a cycle of emotional eating.

Serotonin, another neurotransmitter, is known for its role in mood regulation.

Low serotonin levels are linked to depression and anxiety, and interestingly, carbohydrate consumption appears to increase serotonin levels, providing a temporary mood boost.

This may explain why individuals under stress or with low moods may crave carbohydrate-rich foods.

The Hormonal Response and Stress

When discussing the science behind emotional eating, it is essential to address the role of stress and the body’s hormonal response.

The stress hormone cortisol plays a vital role in emotional eating.

When you’re stressed, your body produces more cortisol, which can stimulate appetite and increase cravings for high-sugar, high-fat foods.

Moreover, elevated cortisol levels can lead to increased abdominal fat storage, contributing to obesity.

The Role of Leptin and Ghrelin

Leptin and ghrelin, two hormones that regulate hunger and satiety, also play a role in emotional eating.

Leptin signals satiety, telling your brain when you’ve had enough to eat, while ghrelin signals hunger.

However, chronic stress and lack of sleep can disrupt the balance of these hormones, leading to increased ghrelin levels and decreased leptin levels, which can result in overeating.

The Gut-Brain Axis

Recent research has also pointed to the role of the gut-brain axis in emotional eating.

The bacteria in your gut can influence your brain and behavior through various mechanisms, including the production of neurotransmitters and the modulation of inflammation.

Some evidence suggests that an imbalance in gut bacteria may contribute to emotional eating and obesity.

Section Summary

The science behind emotional eating is multifaceted, involving a complex interaction of genetics, neurobiology, hormones, and gut health, as well as psychological and environmental factors. Understanding these mechanisms can guide the development of targeted interventions to address this behavior.

Genetics of Emotional Eating

The impact of genetics on emotional eating has garnered increasing attention as a critical area of investigation in the realm of obesity and eating disorder research.

The interplay between genes and behavior is complex, but recent studies have highlighted several specific genetic variants that may influence susceptibility to emotional eating.

A table highlighting common Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with emotional eating, including a brief description of their roles and effects:

| Gene | SNP | Risk Allele | Associated Trait | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTO | rs9939609 | A | Increased BMI, obesity, and emotional eating | The FTO gene is linked to higher body mass index (BMI) and increased risk of obesity. The risk allele (A) for SNP rs9939609 has been associated with greater food intake and preference for high-calorie foods, which can contribute to emotional eating behaviors. |

| DRD2 | rs1800497 (Taq1A) | A1 (T) | Reduced D2 receptor density, increased risk of emotional eating | The DRD2 gene influences the number of dopamine D2 receptors in the brain. The risk allele (A1 or T) for SNP rs1800497 leads to lower dopamine receptor density, which can result in a need to consume more food to achieve the same level of pleasure, potentially leading to emotional eating. |

| 5-HTTLPR | N/A | S (Short) allele | Higher emotional reactivity, potentially increased risk of emotional eating | The 5-HTTLPR gene variant affects the serotonin transport system, which is crucial for mood regulation. The S (short) allele has been linked to higher emotional reactivity, potentially increasing the risk of emotional eating behaviors in response to stress or negative emotions. |

The Role of Appetite Regulation Genes

A group of genes involved in appetite regulation plays a key role in emotional eating. For instance, the Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) gene is one that has been closely studied in this regard.

Variants of the FTO gene have been linked to increased BMI and obesity risk, largely through their influence on food intake and preference.

Researchers believe that the FTO gene may enhance the hedonic response to food, making certain types of food more rewarding.

Therefore, individuals with certain FTO gene variants may be more prone to emotional eating, often gravitating towards high-fat, high-sugar foods that provide immediate pleasure.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the FTO gene variants

The Dopamine System and Reward Response

Another key player in the genetic basis of emotional eating is the dopamine system, specifically genes that regulate the activity of dopamine receptors.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter associated with the brain’s reward system, contributing to feelings of pleasure and satisfaction.

The Dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) gene, in particular, has been implicated in emotional eating.

Studies have shown that certain variants of the DRD2 gene may lead to lower dopamine receptor density.

This could result in individuals needing to consume more of a rewarding substance, such as food, to achieve the same pleasurable effect, thus leading to overeating, particularly in response to stress or negative emotions.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the DRD2 gene variants

Impulse Control Genes

Impulse control is another critical factor in emotional eating.

Genes involved in impulse control, such as those influencing the activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin, can also affect susceptibility to emotional eating.

For example, a common variant in the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) has been linked to higher levels of emotional eating.

The serotonin system plays a crucial role in mood regulation and impulse control.

Therefore, imbalances in this system could potentially lead to impulsive eating behaviors in response to emotional triggers.

While the genetic contributors to emotional eating are substantial, it is important to note that genetics only accounts for a portion of the risk.

Check your AncestryDNA, 23andMe raw data for the 5-HTTLPR gene variants

Section Summary

Emotional eating is a multifaceted behavior influenced by a range of environmental and psychological factors, as well as these genetic predispositions.

Therefore, a comprehensive approach that addresses all these aspects is essential in effectively managing emotional eating.

Non-Genetic Contributors To Emotional Eating

Although genetics can predispose someone to emotional eating, it doesn’t necessarily mean they will develop this behavior.

Environmental and psychological factors

Environmental and psychological factors also significantly contribute.

Emotionally driven eating is often linked with stress.

The body’s stress response triggers the release of cortisol, a hormone that stimulates appetite, particularly for high-sugar, high-fat foods.

As a result, individuals undergoing chronic or acute stress may find themselves turning to food for comfort or distraction.

Psychologically, negative emotions such as sadness, loneliness, and anger may trigger emotional eating.

Emotional eating can also be a coping mechanism for individuals dealing with depression or anxiety, using food as a way to momentarily escape their troubling feelings.

Social and cultural factors

Furthermore, societal and cultural factors cannot be overlooked.

The media’s portrayal of food as a source of comfort and reward, coupled with the easy availability of ultra-processed foods, facilitates emotional eating.

Recommendations To Overcome Emotional Eating

Overcoming emotional eating requires a multifaceted approach, including behavioral changes, psychological interventions, and potentially genetic counseling.

- Mindful Eating: This is a practice of intentionally focusing on the present moment while eating. It encourages individuals to savor their food, pay attention to their hunger and satiety cues, and helps dissociate eating from emotional triggers.

- Coping Mechanisms: Identify alternative coping mechanisms for stress and negative emotions, such as exercise, meditation, or engaging in a hobby.

- Therapy: Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can be effective. It works by helping individuals identify their triggers for emotional eating and develop healthier responses.

- Genetic Counseling: For those with a genetic predisposition to emotional eating, genetic counseling may provide insight into their susceptibility and potential strategies to manage it.

Wrapping up

Emotional eating is a complex behavior influenced by genetic, environmental, and psychological factors.

While certain genes may predispose individuals to emotional eating, stress, negative emotions, and societal influences significantly contribute.

Strategies such as mindful eating, therapy, and alternative coping mechanisms can help manage emotional eating, especially when personalized to an individual’s needs.

References

- Konttinen, H., et al. (2015). “Emotional eating and physical activity self-efficacy as pathways in the association between depressive symptoms and adiposity indicators.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

- Loos, R.J., et al. (2008). “Common variants near MC4R are associated with fat mass, weight and risk of obesity.” Nature Genetics.

- Meule, A., et al. (2012). “Food addiction and bulimia nervosa

- Klump KL, Keel PK, Racine SE, et al. (2013). “The interactive effects of estrogen and progesterone on changes in emotional eating across the menstrual cycle.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

- Evers C, Marijn Stok F, de Ridder DT. (2010). “Feeding your feelings: emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

- Dallman MF, Pecoraro NC, la Fleur SE. (2005). “Chronic stress and comfort foods: self-medication and abdominal obesity.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.

- Konttinen H, Silventoinen K, Sarlio-Lähteenkorva S, Männistö S, Haukkala A. (2010). “Emotional eating and physical activity self-efficacy as pathways in the association between depressive symptoms and adiposity indicators.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

- Tryon MS, DeCant R, Laugero KD. (2013). “Having your cake and eating it too: a habit of comfort food may link chronic social stress exposure and acute stress-induced cortisol hyporesponsiveness.” Physiology & Behavior.

- Berthoud HR, Morrison C. (2008). “The brain, appetite, and obesity.” Annual Review of Psychology.

- Felsted JA, Ren X, Chouinard-Decorte F, Small DM. (2010). “Genetically determined differences in brain response to a primary food reward.” Journal of Neuroscience.

- Loos RJ, Yeo GS. (2014). “The bigger picture of FTO—the first GWAS-identified obesity gene.” Nature Reviews Endocrinology.

- For recent research findings, here are some references:

- Zhang Y, Cantor RM, MacFie J, et al. (2011). “Common variants in FOXP2 are associated with measures of obesity and binge eating in females.” Molecular Psychiatry.

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. (2012). “Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behavior.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

- Monteleone P, Maj M. (2013). “Dysfunctions of leptin, ghrelin, BDNF and endocannabinoids in eating disorders: beyond the homeostatic control of food intake.” Psychoneuroendocrinology.

- Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, McNulty SG, Driscoll DJ, Butler MG, White RA. (2007). “Whole genome microarray analysis of gene expression in subjects with fragile X syndrome.” Genet Med.

- Sookoian S, Gemma C, García SI, Gianotti TF, Dieuzeide G, Roussos A, Pirola CJ. (2008). “Short allele of serotonin transporter gene promoter is a risk factor for obesity in adolescents.” Obesity.

Written By

Share this article